-

play_arrow

play_arrow

PUKfm

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

London Calling Podcast Yana Bolder

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Summer Festival Podcast Robot Heart

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Electronic Trends Podcast Aaron Mills

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

New Year Eve Podcast Robot Heart

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Techno Podcast Robot Heart

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Flower Power Festival Podcast Robot Heart

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Tech House Podcast Robot Heart

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Winter Festival Podcast Robot Heart

Mhlengi Khumalo

@into.mbiyakwkhumalo

North-West University (NWU) Gallery collaborated with the Social Anthropology subject group and the second-year Graphic Design students to give us the first-ever Zine Fest, which happened on Monday, 20 October, at the new gallery location, F16G. According to the Barnard Zine Library, a zine is short for fanzine or magazine — a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) subculture publication usually made from paper and reproduced through a photocopier or printer.

What started out as a small stall in front of the gallery, evolved into a full-on art exhibition when the gallery found an opening in its busy calendar of exhibitions. The theme of the exhibition was exploring zines as “open forms of decolonial writing and making.” The event started at 16h00, with Ms. Sheryl Msomi, the curator, welcoming guests on the ground floor and thanking everyone for finding the time to attend. She then gave the floor to Ms. Pia Bombardella, a junior Social Anthropology lecturer, who gave a speech. After Bombardella’s speech, Msomi allowed guests to grab something to eat and drink before heading upstairs to engage with the zines and students.

When you walked up the stairs and found yourself on the second floor, you were met with multiple smiles behind tables, with neatly laid-out zines on top of them. Some corners of the room had installations with the zines placed beside them. Then there was a huge white table next to the door by the balcony, where the zine-making workshop would take place at 18h00, featuring various mediums and tools.

When we asked Msomi if she thought the zines would connect with students, she said, “The zines cover similar interests between students and what is important to students personally, whether it be nature or a different topic.” We asked her whether students connect more with artworks or installations, and she responded, “Students connect with both. They connect with artworks because they are curious about the technique, and they connect with installations because they can get closer.” She felt that the gallery is a great place for students to get accustomed to the culture and etiquette of art galleries and also a space that can help them regulate emotions and their mental state.

Bombardella explained that this exhibition stemmed from anthropology’s “crisis of representation” and the question, “How can we tell stories of other people’s worlds?” She wanted to challenge her students to see the colonial sensorium in their everyday life, calling the “leafy suburbs” we study in a kind of green or colonial “apartheid.” She also wanted to see if her students could connect the colonial sensorium with nature, specifically plants. “You cannot survive without plants. You literally need them to make the air you breathe.”

She pointed to indigenous knowledge, where non-human beings are considered kin and rivers have rights. She used “implosion,” which is a critical method for revealing how seemingly simple objects are actually dense, interconnected knots of complex, hidden histories, practices, and power relations. Students imploded things they loved: one student analysed ballet, concluding that it is “racist” and “sexist,” but they still love ballet, while another imploded their favorite color, blue. “My goal for the zines was to make you stop in your tracks and maybe make the world look a little bit different,” Bombardella said.

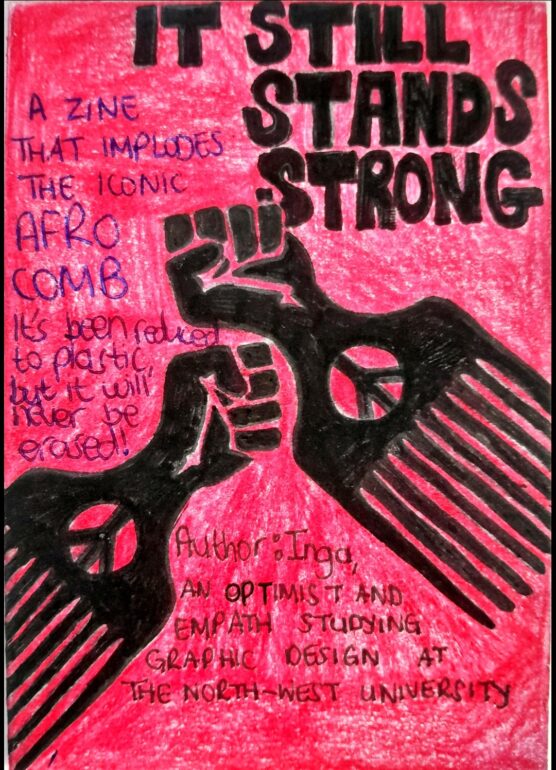

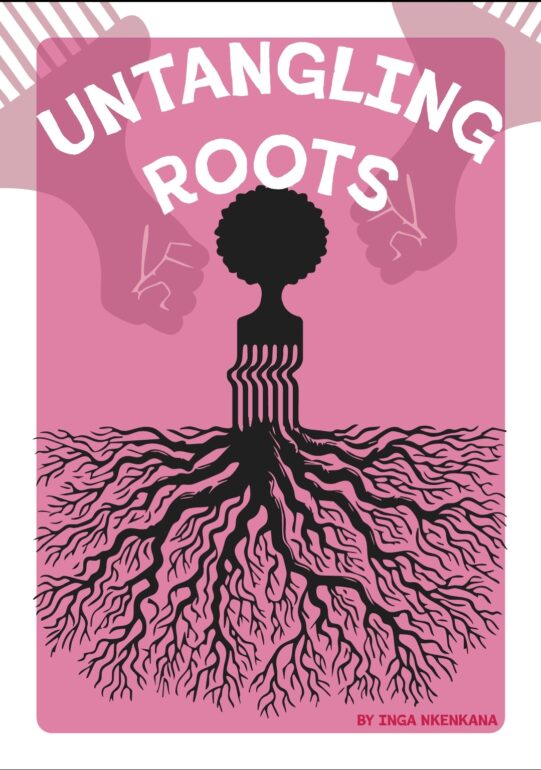

The students really embraced this method, pouring their personal and political frustrations into their work. A core theme seen in the students’ zines was decolonial education, which was highly exemplified in Inga Nkenkana’s zines IT STILL STANDS STRONG and UNTANGLING ROOTS. She used the zine as a “multimodal method to unsettle colonial narratives” by imploding the Afro comb. She reimagined it as a “living archive of resistance, care, and cultural pride.” Her zine traced the Afro comb from its wooden origins to plastic, from its role in unpaid labor to its suppression by “Eurocentric norms.”

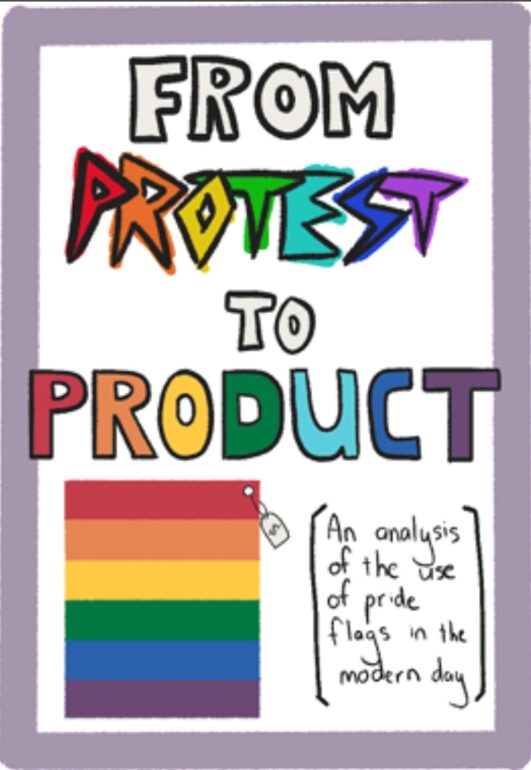

Severyn Jones was inspired by the difficulty of finding people who were inclusive of queer people in Potchefstroom. “I noticed that there are not a lot of really safe spaces in Potch to be openly queer,” he said. His message is simple: “Queer people exist and we just want to be accepted.” His first zine, FROM PROTEST TO PRODUCT, traced the history of the Pride flag. It began with its origins with Gilbert Baker and the Stonewall Riots of 1969 and critiques “Rainbow Capitalism,” where companies like AT&T, Target, and Comcast use the flag for marketing while supporting anti-LGBTQ+ politicians.

His second zine, HOW NOT TO BE AN A-HOLE, argues that your colonial sensorium is not neutral but was trained through white, Western, capitalistic, and cis-hetero norms. It states that colonialism taught us to see queer voices as “loud.” He notes that “before colonialism, queerness was not just accepted but was rooted in sacred, fluid, and reciprocal ways of being.” The zine uses plant parallels like monoecious corn and sex-changing palm trees to show that “nature does not demand boxes, it just grows.”

Keletso Motaung, also known as Kels, created ART GROWS ON TREES, a visual zine connecting pencils and paint to nature. His second zine, dear human., explored learning as a human experience. The zine calls the ability to choose a “blessing” or “curse,” stating that humans always choose themselves first. He calls the “I want” impulse a colonial idea and contrasts it with plants and how well they work together. “The main challenge for me was mostly time and having to break your own biases,” he said. Motaung used digital media because it is affordable and accessible.

Akhona Kunene’s work focused on patriarchy. Her message is that “though women are abused, excluded, and minimized by patriarchy’s design, they still keep the world moving.” If her zine had a soundtrack, it would be Be Alive by Beyoncé. Her first zine, TO THE MENACE THAT STILLS THE YEARNING OF MY SKIN, is about shea butter. She contrasts its healing properties with the labor of the women in West Africa who produce it, facing “gender bias and exploitation” and a banquet of abuse. She wrote, “Woe to me, for their pain makes me whole.”

Her second zine, SHE. HER. ME., is a direct confrontation of patriarchy, countering phrases like “she belongs in the kitchen.” She discussed “brain chauvinism,” the Taliban banning education for women, and South African gender-based violence (GBV) statistics (957 women murdered and 10,191 rapes reported between July and September 2024). She celebrates women, including her mother, as superhumans and history-shaping figures like Susan B. Anthony and Malala Yousafzai.

Msomi’s ultimate wish was that guests would be inspired to create something after they left, and her wish was granted when a large crowd gathered around the zine-making table to partake in the activity. Elizma Stoltz and Sunelle Bührmann, second-year Graphic Design students, organized and facilitated the zine-making session, giving everyone a step-by-step guide on how to make a zine while also allowing them to run wild with their designs, even providing prompts to get the creative juices flowing.

Since the crowd was so large, people were allowed to team up and were given 30 minutes to create their zines and showcase them afterward. Bombardella said, “There is nothing scarier than a blank piece of paper, and it is lovely to see their first zines and look at the amazing stuff that came from risk-taking.”

Given the exhibition’s success, both Msomi and Bombardella would like to host another Zine Fest next year. We would love to see another Zine Fest, as it not only inspired us but also left us having learned something about plants, social experiences, and imploding our mindsets.

Edited by Simoné de Witt

Written by: Wapad

Similar posts

Recent Comments

Chart

-

-

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

I Had Some Help (feat. Morgan Wallen) Post Malone

-

-

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Not Like Us Kendrick Lamar

-

-

Top popular

VARSITY CUP TICKET RESELLERS AND BUYERS – MAY BE DENIED ACCESS

UNANSWERED AND UNSPOKEN: NWU’S SILENCE ON SUSPENSION OF SCC STUDENT LEADER

NWU EXPELS STUDENT LEADER AFTER INTERNAL FINDING OF SEXUAL MISCONDUCT

MARCHING FOR JUSTICE AND POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY: THE TRUTH BEHIND THE TMM LOFTS PROTEST

DEGENAAR PRAAT OOR DIE NA-SKOK VAN ‘N TRAGEDIE

Post comments (0)